Inside the US push to uncover Indigenous boarding school graves | Indigenous Rights News

San Francisco, California – Phil Smith’s parents dropped him off at the Charles H Burke Indian School in New Mexico when he was five years old, in 1954.

A member of the Navajo Nation, Smith would attend the boarding school just outside the nation’s borders for one year, before moving onto other similar schools in the United States.

He spoke the Navajo language when he arrived but was taught that it “was no good, it’s not useful, (and) you need to only learn English”, explained Smith’s daughter, Farina King, who shared his story with Al Jazeera.

As a result, Smith didn’t teach King or her siblings the Navajo language. “And then I don’t learn Navajo, and I’m placed in this very difficult position where I’m the one who has to do this reconnecting work,” she said.

Hundreds of schools

In 1927, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a federal government agency, converted former army buildings at Fort Wingate, about 210km (130 miles) west of Albuquerque, into the school for Navajo and Zuni children.

In the 1860s, the ancestors of the Navajo students had been forced to march in what is known as the “Long Walk” to Fort Sumner, where they were confined. One-third died of disease and starvation.

According to a researcher who visited the Charles H Burke Indian School in 1927 as part of a survey of Indian boarding schools in the US, a Navajo girl died from tuberculosis the morning of his visit.

In The Meriam Report, a survey of the living conditions for Native Americans across the country, Lewis Meriam wrote that the school “was as distressing as any place I have visited”.

The US government ran at least 367 schools (PDF) like this one – forced assimilation institutions that aimed to exterminate Indigenous language and culture, according to the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. The US operated 25 of these schools and supported hundreds more that were run by churches, most often the Catholic Church.

Federal investigation

In June, following the discovery of hundreds of Indigenous child graves at Kamloops Indian Residential School in western Canada, US Interior Secretary Deb Haaland ordered a federal task force to investigate graves at the schools.

That was when King said she realised that she exists today because her father and ancestors survived the institutions.

“In the United States there needs to be a real acknowledgement across the board with critical masses – not only top-down from the government, but how do we get Americans of all walks of life and backgrounds to understand the significance of this?” King said.

Now, the search is on for missing children and graves in the US. Native American communities have long known that graves existed at the sites of the former boarding schools, and they have been carrying the weight of survivors’ trauma for generations.

In July, the remains of nine Lakota children who died at the government-run Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania were returned to their families.

Earlier this month, the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition – the group that has pushed for six years for the government to release boarding school records – announced it would collaborate with the Department of the Interior on its investigation.

The department is now consulting with Indigenous communities, including tribal governments, Alaska Native corporations and Native Hawaiian groups, on key issues to be included in its report, a spokesperson wrote in an email. The consultation will also lay a foundation for future site work to protect potential graves.

“Topics being discussed include appropriate protocols on handling sensitive information in existing records, potential repatriation of human remains, and management of sites of former boarding schools,” the spokesperson wrote.

The task force is expected to deliver a report by April 1 next year.

‘They most definitely have graves’

The schools, which operated from the late 1800s until the 1970s in the US, were part of a policy that forced Indigenous people from their land and onto reservations. In an 1892 speech, US Army officer Richard Pratt, who founded one of the first schools, described the policy as: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

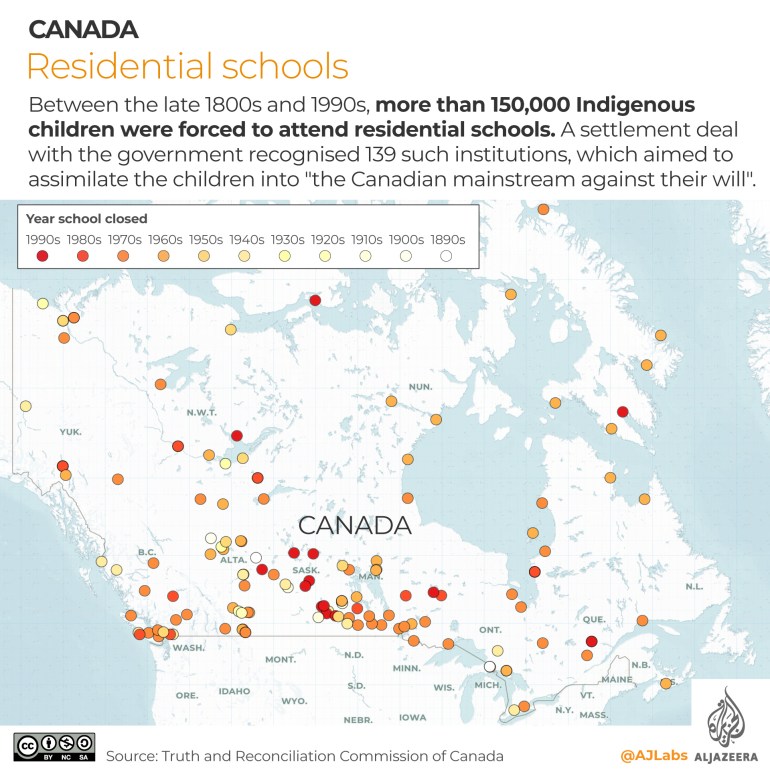

The US system inspired Canada’s similar network of so-called “residential schools“; in an 1879 report, Canada’s then-Minister of the Interior Nicholas Flood Davin recommended Canada adopt the US Indian boarding school system.

From 2008 to 2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission gathered testimony from 7,000 survivors of the institutions. The Indian Residential Schools settlement agreement compensated students who attended 139 schools across Canada. An estimated 150,000 First Nation, Metis and Inuit children passed through the system, and the commission estimated that 6,000 children died at the schools from disease, starvation, abuse, fires, and other causes.

Christine McCleave, CEO of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, told Al Jazeera she hopes the US task force, along with a bill before Congress to establish a truth commission, will result in the US government hearing survivors’ testimony, similarly to what happened in Canada.

The US had at least twice the number of schools as Canada did, so McCleave said she believes at least twice as many Indigenous people passed through the institutions. She also predicted the US government would likely discover that most of the schools have graves associated with them.

“If they were open at the turn of the century, then they most definitely have graves, because there was a high rate of student deaths from tuberculosis and influenza – preventable diseases,” she said.

Canada’s commission declared the schools amounted to cultural genocide, and McCleave wants a similar declaration from the US. “Anybody can look at the United Nations definition of genocide and see that the United States has done all of those things to Indigenous peoples in this country.”

Protocol for searches

Marsha Small, a northern Cheyenne researcher, did a survey in 2019 using multiple scanning tools that found a total of 222 graves at the site of the former Chemawa Indian School in Oregon.

That total included 210 graves associated with the boarding school, Small said, while community members unconnected to the boarding school era were also buried in the cemetery.

Small has interviewed survivors about harsh punishment at the school; one person said her father still had scars from being whipped at Chemawa, Small told Al Jazeera. “They really were concentration camps, they really were prisons,” she said of the schools.

It was a genocide, she said. “It’s an eradication of our people.”

Together, Small and King are developing protocols for how to respond when graves are discovered at the boarding schools. King said they have shared these protocols with the Navajo Nation.

When remains are found, they likely come from multiple nations, and each nation has different protocols for how to respond to graves, Small said. Some nations want ground-penetrating radar used, while others do not want their children disturbed in any way. “They might be buried right next to each other,” she said.

Meanwhile, McCleave and Small also are calling on the federal government to establish a crisis hotline for survivors of the institutions. “The Band-Aid has been ripped off, the scab is exposed, pulled off, and now it’s a raw wound,” Small said.

The Department of the Interior told Al Jazeera that the federal Indian Health Services is working with Native leaders to develop culturally appropriate resources to support those who may experience trauma resulting from the task force investigation.

McCleave said she hopes the April report will specifically mention which schools have graves associated with them. “I do see this as a very hopeful beginning to a long road that we have ahead of us of truth and healing,” she said.

Pingback: stapelstein

Pingback: เว็บตรง bk8

Pingback: บอลยูโร 2024