Lost to Alzheimer’s: Losing Mom but finding her magic cheesecake | Mental Health

At a time when so many are dealing with the loss of a loved one, our new series, How we remember them, explores what it means to lose – and to remember – someone.

The house was a museum. My dad was the curator.

Her clothes filled the closets. Dresses were hung, pants pressed, sweaters neatly folded and stacked. Her wooden-handled hairbrush remained next to the bathroom sink. The refrigerator door was a collage of scrawled notes — emergency contacts, daily to-do lists, a funny comic she enjoyed.

My dad was prepared for my mom to come home any day, even though years earlier she had moved into a nursing home full time.

“They’re always making progress with Alzheimer’s,” he’d say. “You never know what can happen.”

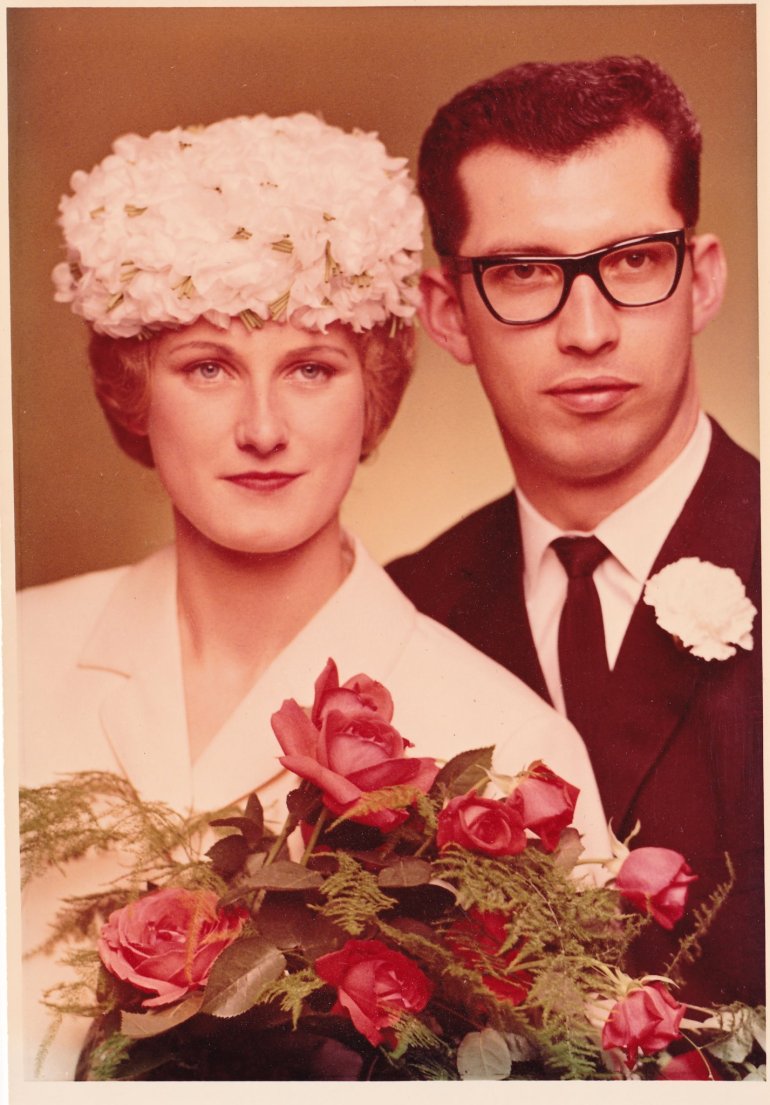

A photo of the writer’s parents on their wedding day in May 1962 [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]

A photo of the writer’s parents on their wedding day in May 1962 [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]He left his true hope unsaid: that someone would find a cure. They’d make a pill. It would go away. Mom’s mind would snap back into her body, and we’d look back on this and marvel, “Do you remember that time you forgot all of us? That was wild.” We’d hug her and warn, “Don’t do that again. You scared us.”

That’s why, at the time of her death, there were still purses, shoes, bottles of hairspray. Quilts, receipts, photographs, a china cabinet filled with items we never used. Powders and creams, pots of eyeshadow, a perfume gone rancid. All the evidence of a normal, everyday life. Almost everything was there except Mom.

• • •

Before my mom moved into the nursing home, back when she was still in the early to mid-stages of the disease, she received in-home care while my dad went to work, ran errands, and kept the household tethered.

The in-home care provided basic companionship, assistance with special tasks like making lunch, and a comforting presence. That last bit was important since my mom’s dementia manifested with a heavy dose of paranoia.

My mom thought airplanes were beaming secret messages on the rooftops of houses in our neighbourhood. She saw patterns in the frequency and colours of cars driving down the street, and they frightened her. When the phone rang with a wrong number, she imagined it was part of a convoluted plot. The world, it seemed, was conspiring against her.

She had flashes of jarring lucidity, followed by weeping. In these moments, she’d hold her head in her hands.

“It hurts,” she once cried. “My head. It hurts. Why is this happening?”

It hurt me that I couldn’t offer any answers. The more I tried to explain, the more she believed the vast conspiracy was closing in. She was violent and hard to calm, but I couldn’t blame her. The world is often confusing and frightening to those of us who are fully aware; imagine how daunting it must be when you’re not.

The writer with her mother [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]

The writer with her mother [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]When Mom said her caregiver was stealing things, we didn’t believe her. Not until a few days after her funeral, when we emptied her jewellery boxes on the floor and realised her valuables were gone. The rings with opals set among diamonds. The gold watch. A ruby bracelet. One of the shiny cocktail rings she reserved for special occasions. The things left behind were cheap baubles.

It pains me to know that as my mom was losing things, she knew it. She was aware that someone was stealing her jewellery, and she couldn’t stop it. It’s possible she knew other things were being stolen from her as well, that she understood her mind was taking flight.

We always focus on what is forgotten by the person with Alzheimer’s. But what about the things they remember?

• • •

Alzheimer’s disease tampers with everything inside a body, right down to the taste buds.

It’s like eating when you have a terrible cold, one of my mom’s doctors explained. When taste is dramatically impaired and the palate is dulled, only powerful flavours can break through. So as my mom’s disease progressed, she couldn’t delineate between most flavours, but she could still appreciate food that was syrupy sweet.

For my mom, her taste preferences leaned heavily on the sweet side anyway. She loved pastries and cakes, chocolate bars and apple fritters. Later, towards the end of her life, her diet included applesauce, chocolate pudding, and overcooked vegetables with white sugar sprinkled on top.

That’s the one minor kindness of a terrible disease. When everything else disappears, sweetness remains.

• • •

It’s a week after her death. Three siblings sprawled on the floor.

Dad asks us to go through Mom’s stuff, to see if there’s anything we want before he packages everything up to donate.

We open the jewellery box, tiny wooden doors that swing open and little drawers lined in red, silky fabric. She also kept jewellery in shoeboxes, and we dump the contents of those on the carpet, making small mountains of costume jewellery. She had a weakness for sparkly things and hoarded them like a crow building a nest.

The writer (left) with her siblings [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]

The writer (left) with her siblings [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]Each item moves me through time. There are plastic necklaces with plump, fake stones, and I’m a kid at a Fourth of July celebration, carrying potato salad to the block party. Next I’m in a small jewellery shop in Germany while my mom purchases an amber broach that is shaped like a spider. One long string of polished amethyst chips takes me to church on Easter Sunday. My mother’s dress is violet, billowy, and the air is laced with the scent of hydrangeas.

The terrible thing about memory is that it’s impossible to control.

Most of my early memories of Mom have been replaced by the memories of losing her. I remember her slouched in a wheelchair, not driving a car. I see her head lolling against her chest, not telling me a story and kissing me goodnight.

But occasionally I conjure her vibrant and active and lucid, and I am greedy with the memory. Sometimes it’s a witchcraft of the senses — a taste that transports me to a moment or a smell that immerses me in a place. Other times she comes to me in dreams, doing remarkably normal things. She’s vacuuming, putting something in the oven, teasing her hair into a curly blonde halo. I wake up crying but satisfied.

On the floor with my siblings and the fragments of my family, I pull a necklace over my head. It envelops me in the heavy scent of a perfume I always hated, and I try to stay there, curled up in a fragrance the way I once curled up in her lap.

• • •

None of us is up to the task of sorting. We can’t possibly sell the jewellery – the pieces aren’t worth much, if anything. There’s too much to keep. But we don’t want to give them away, either. They are too evocative of Mom.

“You know what I’d really like?” my brother says.

He’s the capitalist among us, so I expect him to say he wants to track down the valuable jewellery. The gold watch. The rubies.

“Mom’s cheesecake recipe,” he says.

My sister and I nod. That cheesecake was spectacular.

The writer’s family at her sister’s wedding in Dayton, Ohio in March 1983 [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]

The writer’s family at her sister’s wedding in Dayton, Ohio in March 1983 [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]It wasn’t a fancy dessert. It was dense and heavy, basically bricks of cream cheese smoothed into a springform pan. It often ended up cracked and lopsided, a behemoth of dairy. The edges were dark. The centre sank, moist and pale.

There’s no doubt the cheesecake was unattractive. If this thing arrived on your table at The Cheesecake Factory, you’d assume there had been a mishap at the actual factory. A broken machine, maybe, or a cheesecake inspector sleeping on the job.

We were tolerant of the cake’s faults, though, because it was delicious. Thick and substantial, slightly tart but mostly sweet.

Also we were a family that clipped coupons and recycled soda cans for the money. Our trips to the grocery store didn’t involve many treats, because we couldn’t afford to stray from the basics.

That’s another reason we loved the cheesecake. For the taste, sure, but also because it was richer than anything we’d ever eaten before. It was the kind of dessert that implied decadence. It was the Golden Girls in their swank Miami condo, hunkered over a delectable thing. It was the breezy indulgence of ladies who lunch, the kind who say, “Oh, I shouldn’t …” A guilty pleasure for others, but for us, just pleasure.

It was the opposite of following my mom around the market with a calculator, adding up each item that went into our cart. And it was a signpost of my childhood, even though she couldn’t have made it more than three or four times. The cheesecake was rare, which only added to the family legend.

“That recipe is gone,” my pragmatic sister says. “It died with Mom.”

My mom owned few cookbooks over the years: The Joy of Cooking, some collection from Better Homes & Gardens, and a spiral-bound mishmash of recipes from her church. We already know the cheesecake recipe isn’t inside any of those books. We’ve looked.

My sister is right. The cheesecake is yet another thing that has been lost to Alzheimer’s.

• • •

My dad pulls my mom’s purse from the closet and dumps it near the jewellery.

“Here, sort through this while you’re at it,” he says.

We’re swapping stories about Mom as we pluck things from her purse. I am acquainted with this bag, she carried it for years, but now it feels invasive to rummage through it.

There are folded tissues. Lipsticks worn down to coral pink nubs. A compact of face powder that spills fine ivory dust. I can’t remember the last time Mom wore makeup. I wonder when she stopped putting it on her face. I wonder how much of her future she anticipated.

The writer with her mother on her third birthday [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]

The writer with her mother on her third birthday [Photo courtesy of Maggie Downs]My brother pulls out a wallet, the colour of oxblood, fattened with receipts and old layaway slips. The leather is cracked. The magnetic closure falls open. Inside the wallet is a clear plastic insert with several windows for photos.

I know this wallet well. Over the years I’ve lifted it from Mom’s purse dozens of times — pinching a dollar here and there for toys, then cigarettes, then Boone’s Farm Strawberry Hill — so I already know what to expect. There’s my senior picture from high school, some awkward family photos taken at the Sears portrait studio, snapshots of my nephews and nieces as toothless babies.

Only now, tucked inside a clear pocket, is something I’ve never seen before — a piece of paper with my mom’s handwriting. It’s right up front, aching to be found, like she knew.

“Cheesecake,” it says.

For the crust:

1½ cup fine graham cracker crumbs

⅓ cup sugar

⅓ cup melted butter

For the filling:

1 pound cream cheese

1 pound cottage cheese

1½ cups sugar

4 eggs, beaten slightly

2 tablespoons lemon juice

1 teaspoon vanilla

3 tablespoons cornstarch

3 tablespoons flour

¼ pound butter, melted

1 pint sour cream

Mix crust ingredients together and press into the bottom of a 9-inch springform pan. Bake at 350 degrees for 8-10 minutes. Let cool before filling.

While the crust is cooling, beat the cream cheese until light and fluffy. Add cottage cheese, then beat in sugar gradually. Add the beaten eggs, lemon juice, and vanilla.

In a cup, stir the flour and cornstarch together. Slowly beat this into the cheese mixture.

Add the melted butter to the cheese mixture, followed by the sour cream. Mix well.

Pour the mixture onto the crust in a greased springform pan or tube pan.

Bake at 325 degrees until set, about one hour. Turn off oven and leave in for two more hours.

Remove. Chill until completely cool. Enjoy.

Pingback: lion's mane mushrooms order online,