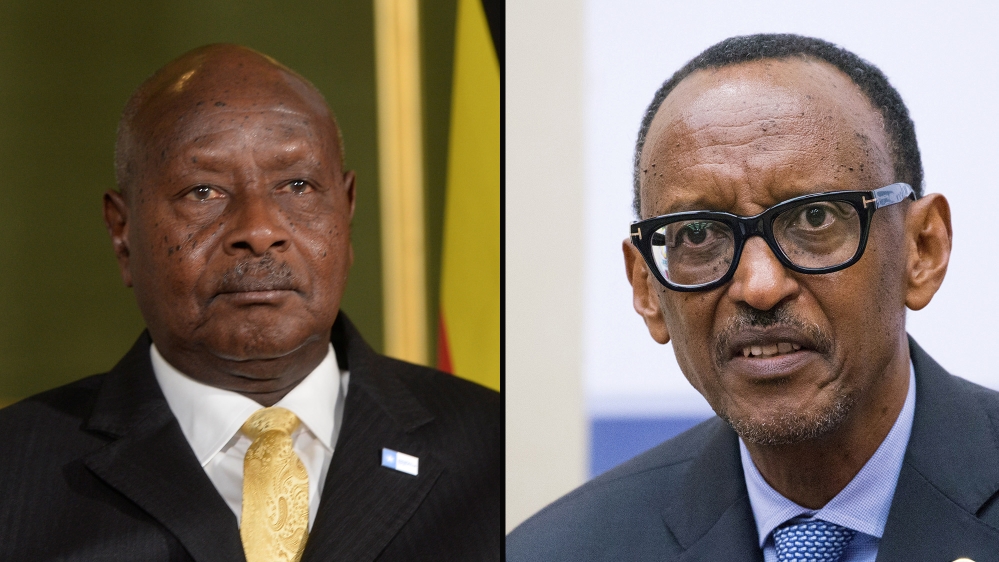

Can Museveni and Kagame’s renewed bromance inspire regional peace? | Features

Kampala, Uganda – Last weekend, Rwandan President Paul Kagame visited Uganda for the first time in nearly four years, a clear sign of thawing relations between the two countries.

Kagame was in Entebbe to attend a birthday dinner hosted by Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni for his son, Lieutenant General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, 48, commander of land forces in the country’s army and a special presidential adviser.

The weeklong birthday celebrations across the country were full of pomp and grandeur.

Kainerugaba, increasingly seen as successor to his father who has been in power since 1986, said he was celebrating partly because of improved relations between both countries.

“We were experiencing bad relations with one of our closest and brotherly neighbours, Rwanda,” Kainerugaba said. “Our relations are good now and are going to even get better. That’s why I think we should celebrate together.”

Last night, I hosted H.E President Paul Kagame, eminent leaders of the Government of Uganda, distinguished guests in their respective capacities, family, friends and relatives to a private dinner in honour of Lt Gen @mkainerugaba. pic.twitter.com/Jnx4HnAoLQ

— Yoweri K Museveni (@KagutaMuseveni) April 25, 2022

The younger Museveni has been at the centre of attempts to mend relations between both countries, having visited Rwanda twice in the past two months and held talks with Kagame whom he calls his uncle.

Those visits led to the reopening of the Katuna border in southwestern Uganda, the busiest border point between the two countries, which Kagame closed in January 2019.

Side by side

Ties between Museveni and Kagame date back to the late 1970s. The latter was one of 27 rebels who launched a bush war in 1981, that brought Museveni to power five years later.

Until 1992, when he and other refugees launched a war that ended in his capture of power in his homeland, Kagame served as a senior military officer in the Ugandan army under his mentor, Museveni.

Since then, the Museveni-Kagame relationship has oscillated up and down. Some analysts have said the disagreements between the two heads of state are ideological, military and a feeling of lack of respect for each other.

Others have argued that the disagreement dates back to the 1980s, when Rwandan refugees felt they were never truly accepted and appreciated for their role in Museveni’s ascendancy to power.

“The tensions between Kagame and Museveni are the kind of frosty relations that you can only find between people with large amounts of intimacy and long history,” Jason Stearns, director of the New York-based Congo Research Group and researcher on conflicts in the Rwanda-Uganda-DRC corridor, told Al Jazeera.

“The relationship that started off as brotherly, then soured and turned into the worst kind of enmity that one can never imagine,” Stearns said.

Perhaps the earliest signs of a deterioration in their relationship came in 1999. Their armies fought each other in Kisangani, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) after disagreeing on a strategy of deposing its leader Laurent Kabila whom they had helped become head of state in 1997.

In 2000, Uganda officially declared Rwanda a hostile state. Both states deployed personnel at border points in anticipation of attacks; Kampala hosted Rwandan citizens considered hostile to Kigali and vice versa.

It took the diplomatic intervention of Clare Short, the then British minister for international development, to get the duo back on good terms.

Tensions flared again in 2005 when Kampala felt Kigali had disrespected Museveni by forcing him to drastically reduce his security detail during the COMESA summit in Kigali. Kagame, in turn, cancelled a visit to Kampala without notice, leaving senior government officials who waited for him at the airport baffled.

The most recent episode of the squabble began in 2018 when Rwanda accused Uganda of giving sanctuary to dissident groups. In response, Uganda accused Rwanda of espionage.

A pact brokered by regional heads of state had little impact. The strain in relations led to border closure by Rwanda for three years, troop deployment adjacent borders by both countries in anticipation of a war and a total breakdown in trade.

The diplomatic strain particularly hit hard businesses at the border, which depended on daily movement of people and goods.

Uganda’s ministry of trade estimated a loss of approximately $200m in export earnings to its neighbour across one year, because of that decision. Six Ugandans were also reportedly killed by Rwanda soldiers allegedly trying to smuggle goods across the border.

Consequently, Kainerugaba’s intervention is being seen as a double-edged sword.

Though relations are improving, Solomon Asiimwe Muchwa, professor of international relations at Kampala’s Nkumba University said that Uganda could find itself in a situation where nothing is discussed and agreed upon with Rwanda if Museveni or his son does not intervene.

“The issue of relations between the states should be at national level,” Muchwa said. “Muhoozi went to meet Kagame not as an army official. He went as the son of the president.”

And going forward, stabilising relations between the two countries will depend on how Rwanda views Uganda’s response to its security interests, observers said.

On his part, Muhoozi’s visit to Kigali led to the removal of an army intelligence chief who was viewed as anti-Kigali and he has pledged to crush anti-Rwanda elements who dare try to establish bases in Uganda.

General Kayumba and RNC, I don’t know what problems you had in Rwanda with the mainstream RPF/RDF? But I warn you not to dare use my country for your adventures! pic.twitter.com/qgYkkvvDg5

— Muhoozi Kainerugaba (@mkainerugaba) February 19, 2022

Angelo Izama, a Kampala-based independent researcher in Kampala said Kainerugaba acted on his own in talking to Kagame – a wildcard move. “Whether or not he is able to sustain this trend going forward is as unpredictable as the impact of his initial involvement is,” he said.

The younger Museveni’s move to reconcile the two heads of state was to make out his own path, regardless of the chequered history between both countries – dominated by the heroics of the older generation – argued Izama.

Regional peace

Nevertheless, a cordial Kagame-Museveni relationship remains crucial to the progress of the East African region, especially in finding a lasting solution to the multiple conflicts in the DRC, its newest member.

Though rich in natural resources, the DRC is one of the poorest countries in the world and since its independence in 1960, the DRC has been mired in a series of conflicts.

After his ascent to power in 2019, DRC President Félix Tshisekedi courted Rwanda and Uganda for support in ending these conflicts.

“The relationship between Uganda and Rwanda is extremely important for security in eastern DRC,” Stearns says. “Wars in eastern Congo have always come with foreign backing particularly from the two countries.”

Last week, the regional heads of state met in Nairobi and agreed to set up a regional force that will be deployed in eastern DRC. The intervention comes at a time when DRC has accused Rwanda of supporting the resurgent M23 rebels.

Kagame missed the forum.

However, in Kampala during the weekend, he agreed for Rwanda to be part of the regional force. It is expected that he and Museveni will want to see peace in the DRC seeing as rebel groups originating from Rwanda and Uganda have had sanctuaries in the eastern Congo for decades.

But even the promise of regional deployment is not a magic wand.

“Tshisekedi and Museveni can’t do anything in isolation of Kagame because he has the capacity to derail whatever intervention is put in place,” Muchwa said.

Last year, President Tshisekedi permitted Ugandan soldiers to enter the region to fight the Allied Democratic Force (ADF) rebels.

Kagame, who is said to have sought for a nod of approval from Kinshasa to deploy and fight rebels of Rwandan descent alongside the Congolese forces, pointed out recently that Kigali’s interests should not have been neglected.

Stearns said Kagame has been frustrated with Tshisekedi because all three countries were to have established a joint police command for intelligence. The initiative never materialised because of protests against it by Congolese.

“There are a variety of reasons why Kagame isn’t happy with the current situation,” Stearns said and that could mean a new round of diplomatic negotiations.