Jurgen Griesbeck interview: Common Goal and the struggle to make football wake up to its global responsibilities | Football News

Football for Peace began in 1997 in Medellin, Colombia. It was regarded as one of the most dangerous cities in the world. A German man named Jurgen Griesbeck wanted to help change that. He proposed that the gangs played football against each other.

There would be no referees. Fouls would be called by consensus. And there had to be men and women on each team with the first goal needing to be scored by a woman. The idea was that it encouraged team play. Everyone had to be valued in order to succeed.

It was radical and at first there was resistance. But it worked.

At its peak, there were 10,000 players. The shirt of Andres Escobar, the Colombian murdered after his own goal at the 1994 World Cup, was worn by all Football for Peace players and came to act as a passport, enabling safe passage through rival territories.

Years later, Alejandro Arenas Tobon, Griesbeck’s partner in averting crime, was back in Medellin and saw a street game being played by Football for Peace rules. The youngsters did not know where they had learned it. The game had always been played that way.

“It is the story I am most proud of in the book,” Griesbeck tells Sky Sports.

The book in question is Radical Football, a history of the football for good movement and a manifesto for what must happen next. It is also part autobiography, the story of how an aspiring academic from Germany came to become one of football’s game-changers.

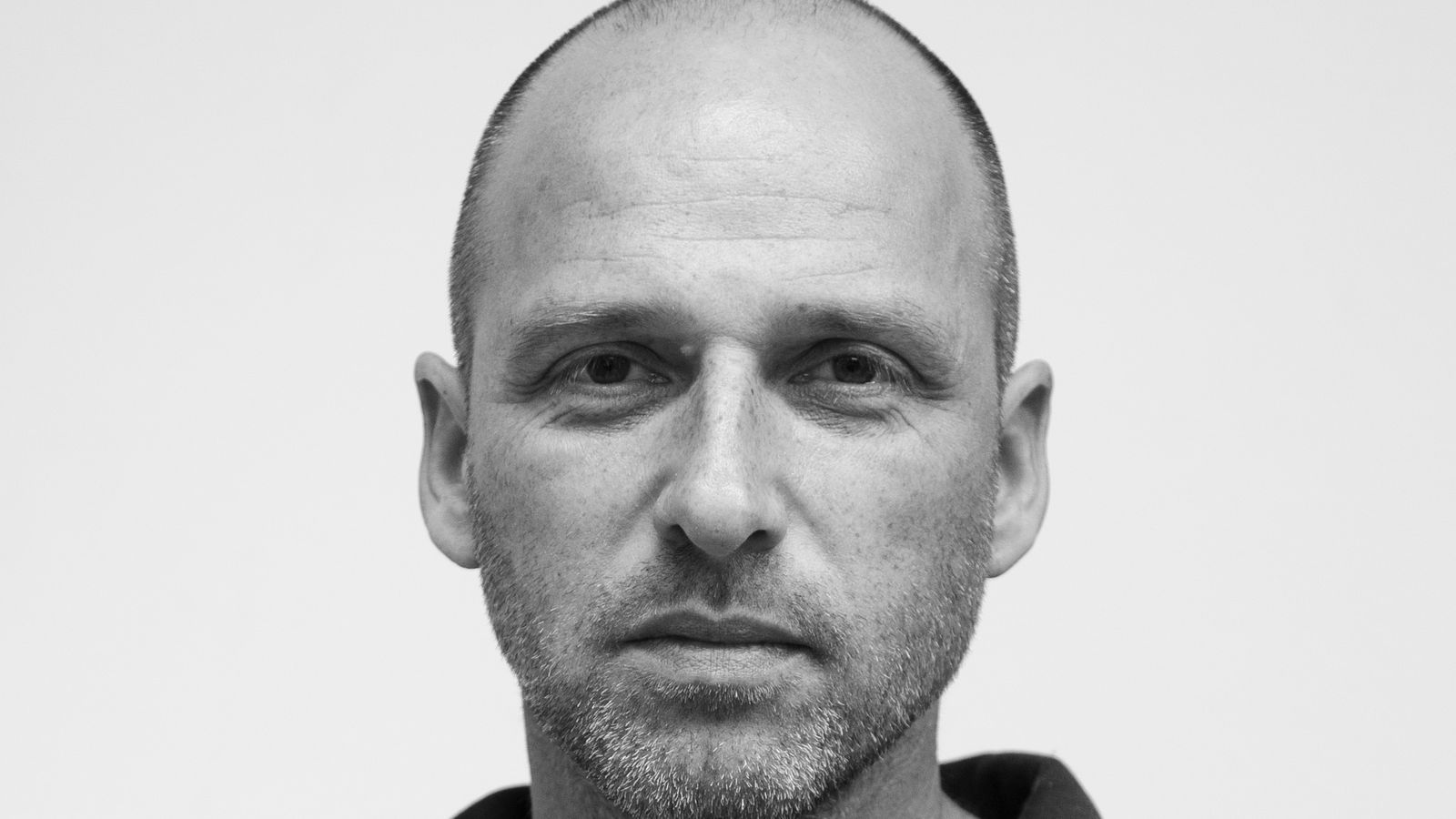

Griesbeck won the Laureus Sport for Good Award in 2006 and went on to found Common Goal with Juan Mata in 2017. But the journey began with Escobar’s shooting in 1994. The moment convinced him to change course. He had to try to make a difference.

“The assassination of Andres is something that, even now, is still there,” he says. “It is not in the front of my mind all the time but I do think it is very deep in me. It is this flame that does not allow me to have a doubt about what needs to be done.”

Medellin was near lawless at the time, in thrall to the drug cartels. “It was easier to hire a killer – a sicadio – than buy a fridge.” Foreigners were regularly kidnapped. But Griesbeck, with the unwavering support of his Colombian wife Elida, set about making change.

“She knew the cultural codes in Medellin. She knew the danger I was exposing myself to. I did not know anything. I was a greenhorn. I was really naive. I never sensed the danger that others told me was there. My wife did. She was the brave one not me.

“We were dealing with serial killers in Colombia but I felt more inspired, more connected, because they allowed themselves to be emotional. Deep down they did not want to live in that situation, they wanted peace, they just did not know how to get it.”

Driving a 1954 Ford, he made himself both conspicuous and low status – the gang leaders had flashier vehicles. “The car helped. Being recognisable was part of my life insurance.”

His role as an outsider also ensured that Griesbeck was listened to by all sides. “There was no obvious reason for me to care about these young people in Medellin,” he explains. “The same trust would not have been deposited in a fellow Colombian.”

A quarter of a century on, his determination to change the world through football remains undiminished. Indeed, the power of the game is more obvious to him than ever before.

“It is the only thing that can do what humanity needs to be done. Religion cannot do it now. No government can do it. The United Nations cannot do it. No music can do it. No cultural phenomenon can do it. There is no other thing. It is football.

“It is the one uniting force that speaks to more than 50 per cent of our population. Football can get to the hearts and minds of people, a critical mass, and it can change how we are as human beings. But it needs to wake up to what it can be. And because it can, it must.”

He is still hopeful that Common Goal can be the catalyst for that change. Members of the movement pledge at least one per cent of their salary to help support good causes around the world. “What changes if our new 100 is 99? Nothing really changes.”

It has been a success. Since Mata kicked it off with his announcement, he has been joined by household names such as Jurgen Klopp, Mats Hummels and Giorgio Chiellini. A natural optimist, Griesbeck prefers to focus on these positives. But it is difficult.

“I don’t know if angry is the word. It may be. There is anger in there. But it is really frustration and disillusionment at some points.” The process of convincing a player to pledge can take nine months. “It is that complicated.” And the answer can still be no.

Griesbeck’s colleague Thomas Preiss arranged a meeting with an agent at a London café that came to an abrupt end when the one per cent figure came up. They find that “the narrative is manipulated” in such a way that they rarely get to speak to the player.

Perhaps it is telling that Common Goal has had more luck with the women’s game. Some of the biggest names have signed up – a list that includes Magda Eriksson, Pernille Harder, Vivianne Miedema, Alex Morgan, Irene Paredes, Megan Rapinoe and Christine Sinclair.

“It is much quicker, easier and more direct with female athletes,” admits Griesbeck.

Men struggle to escape their bubble. “Juan is a very inspiring guy because he does that. But he has to discipline himself. He has to make a real effort not to be absorbed by the bubble. It is hard to get a sense of what you could be doing from inside that bubble.

“I do think the self-awareness of the female player is different. Women, in our experience, they just never disconnect. They do not have the privilege to disconnect.”

He recalls a recent meeting with two international players in the women’s game who have six university degrees between them. “They were saying, ‘I am just playing football, I have so much time, what can I do?’ You will not hear that from the average male player.”

He sees it as a chance missed, even from a PR perspective.

“What we have heard from athletes who have joined the movement is that this offers an opportunity for their followers to engage with them on a personal level. That takes pressure off the player part of their lives because people start to see the person first.”

He cites the example of the Danish club FC Nordsjaelland. “Their statement is that a better person is a better player. But it is not mainstream in football. You still hear people say that a footballer has only 10 to 15 years and they have to just focus on football.”

There is a sense of urgency now. “This incremental stuff is too slow. It needs something radical.” After many years of having to play politics with presidents and club owners, is Griesbeck still that radical? “I would say more and more,” he replies.

“I have thoughts that are not in the mainstream. As humanity, we are not committed enough to the next generation, to the planet. We are aware scalable solutions are there but we just don’t do it. I am a real believer that if we do not have radical change, we will fail.

“If you are not contributing beyond yourself, what is the fairy-tale you are telling your children once you go to sleep? The millionaire of the future will not be the person who has that in their bank account, it will be the ones who saved a million lives.”

There is some hope that the 2030 World Cup, bringing up the 100-year anniversary of the tournament, could yet be a line-in-the-sand moment. It coincides with the United Nations deadline for their sustainable development goals set up in 2015.

History tells Griesbeck that it might not be the case.

“I thought that the pandemic could be this moment,” he says. “I thought it would shake up football quite a bit. But then the Super League was prevented and the status quo seemed better than it was. People just wanted to go back to 2019.

“I thought it would be an opportunity but football is not grasping it. It should be a role model for the rest, moving faster than the rest. But it is just too slow. So it is not a question of whether it is getting better, it is a question of whether it getting better fast enough.”

Perhaps one day, years from now, a footballer will be asked why they are donating one per cent of their salary to good causes. The reply will come that they do not know why, it has always been that way. Until then, football’s radical will continue to persevere.

“The minimum I would ask is for people to listen.”

RADICAL FOOTBALL, Jurgen Griesbeck and the Story of Football for Good, by Steve Fleming. Available now from Pitch Publishing (Priced £14.99)

![Manchester United's Juan Mata and Jurgen Griesbeck have launched Common Goal [MUST CREDIT: Max Cooke]](https://e0.365dm.com/17/10/768x432/juan-mata-jurgen-griesbeck-common-goal_4119783.jpg?20171005094043)

![Juan Mata and Jurgen Griesbeck have launched the Common Goal initiative [MUST CREDIT: Max Cooke]](https://e0.365dm.com/17/10/768x432/jurgen-griesbeck-juan-mata-common-goal_4119204.jpg?20171004133940)

Pingback: Asbestos Abatement Mathias

Pingback: Home Page