Mwai Kibaki, the man who epitomised Kenya’s tragedy | Opinions

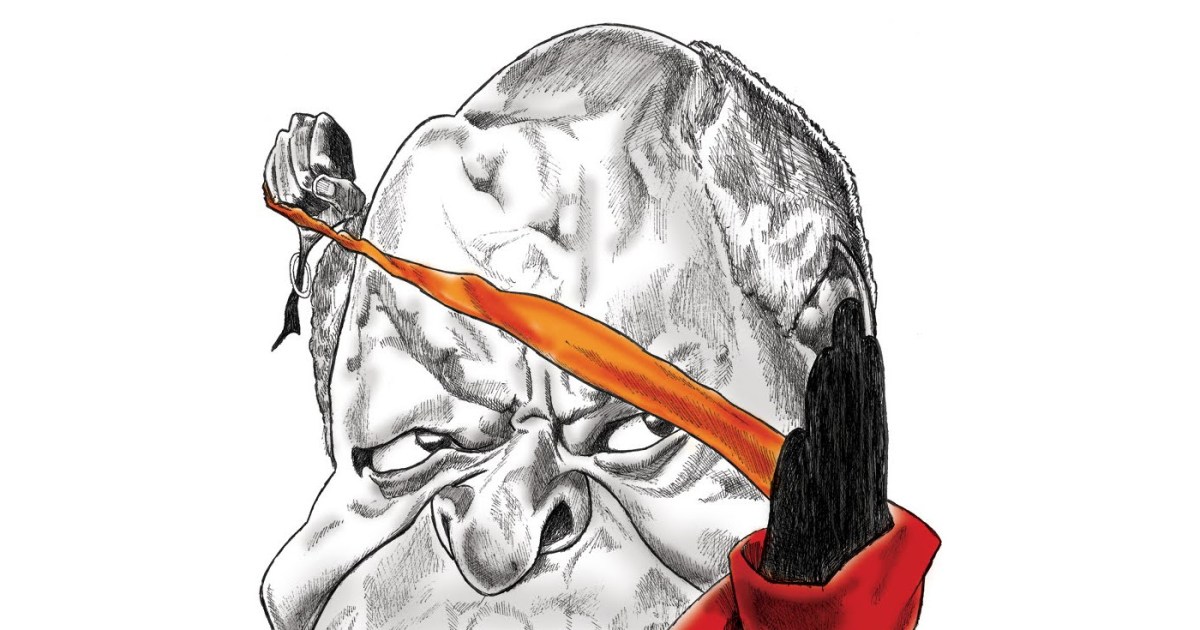

The death of Mwai Kibaki, Kenya’s third president, has predictably elicited a lot of commentaries. There have been the usual hagiographic tributes from politicians and newsmen, extolling him as “the gentleman of Kenyan politics”, praising his custodianship of the country’s economy both as finance minister and president, as well as his supposed integrity. But, and this is somewhat rare, the coverage has not been overwhelmingly cloying. Among the gushing memorials, there have been other prominent pieces laying out his record of cowardice, deception and betrayal, his lust for power that almost destroyed the country and his self-enrichment and tolerance for corruption.

For me, Mwai Kibaki epitomised Kenya’s tragedy. There is no doubting his brilliance – a man who came from the humblest of beginnings, excelled in school and grew to be considered one of the most influential and promising Africans of his generation. But when it came down to it, he was incapable of extricating himself from and confronting the colonial system that had opened doors for him but kept them closed for so many of his countrymen.

“Will the elite, which has inherited power from the colonialists, use that power to bring about the necessary social and economic changes, or will they succumb to the lure of wealth, comfort and status and thereby become part of the Old Establishment?” he asked in 1964, months after Kenya had secured its independence from Britain. Kibaki, who was in government from the very start, as a permanent secretary of the treasury, and eventually as minister of finance, was one of those elites, and as history shows, they happily ensconced themselves in the colonial state and continued its thieving and brutal ways.

With Kibaki running the economy between 1969 and 1982, Kenya did experience an initial period of relative prosperity. However, the shine quickly wore off as growth fell, which at least one study has blamed on “the oil shocks of 1973 and 1979 compounded by poor macroeconomic management, breaking the tradition of fiscal responsibility and prudent monetary policy followed during the early years of independence”.

All along, the Kenyan elite engaged in a spree of self-enrichment. Among them, Kibaki clearly “succumbed to the lure of and wealth, comfort and status” and was happy to serve in the oppressive and kleptocratic administrations of his predecessors, Jomo Kenyatta and Daniel Arap Moi. Despite spending almost his entire working life in public office, he died one of the wealthiest men in the land. And even as he left office in 2013, he engineered an exorbitant and immoral “retirement package” for himself, forcing Kenyans to shell out $2.5 million gratuity payment in addition to tens of thousands more in monthly pension payments and benefits later declared unconstitutional.

Though he showed flashes of courage, such as when distinguished himself by being the sole cabinet minister to attend the funeral of JM Kariuki, a populist politician whom the Jomo Kenyatta regime murdered in 1975, for much of his career it was said that he never saw a fence he did not wish to sit on. He held the dubious honour of having moved the 1982 constitutional amendment that made Kenya legally a single-party state. Undoing that would become the focus of political reform efforts later in the decade, which Kibaki would ridicule as trying to cut down a tree with a razor blade. But once those efforts succeeded in 1991, he was among the first to piggyback on them, abandoning the ruling party, KANU, to form his own outfit.

In 2002, he again benefitted from the reform efforts when he was elected president by a landslide, with an overwhelming mandate to overthrow the colonial system and the corruption it bred. Instead, he bastardised the constitutional review process, leading Kenyans to reject it in a referendum in 2005. He presided over an orgy of corrupt looting that in 2004 was described by the UK ambassador as gluttonous eating. By the end of his first term, he was happy to rip up the “gentleman’s agreement” that five years earlier had allowed opposition parties to nominate members of the election commission, paving the way for his 2002 win. That set the stage for the disputed 2007 elections, which many, including me, believe he stole, and the violence that followed that claimed at least 1,300 lives, displaced hundreds of thousands, and brought the country to the brink of anarchy. Many of those deaths were at the hands of the police he controlled and a murderous gang that the International Criminal Court prosecutor claimed had met with him at State House.

Kenyans tend to look back at the Kibaki years with rose-tinted glasses as a sort of economic “golden age” and, despite all the theft and criminality of his regime, Kibaki himself as competent and exceptional. I have my doubts. When you put together the middling economy; the gluttonous eating; the many scandals and state violence, including attacks on the press; and the watering down of the constitution, his tenure really does not seem very exceptional.

In the end, he proved to be true to the system that made him. It is the same system that made Kenya and that the country has for 60 years been trying to extricate itself from. Cometh the hour, cometh the man, goes the saying. Unfortunately, when Kenya’s moment came, Kibaki turned out not to be the man.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Pingback: จํานําโฉนดที่ดิน ไม่ใช่ชื่อเรา

Pingback: buy botox online 50 units