Five key issues at stake in the Zimbabwe elections | Elections News

Harare, Zimbabwe – On August 23, six million registered Zimbabwean voters will go to the polls to choose the country’s president.

While the focus is mostly on the high-stakes presidential contest, across the Southern African country’s 10 provinces, the electorate will also cast votes for local government representatives and parliament representatives.

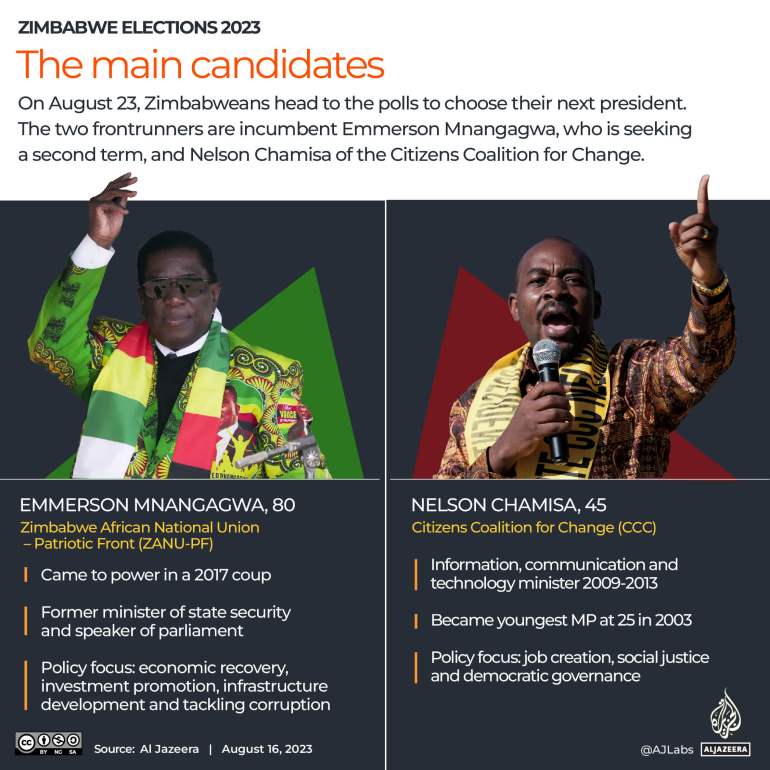

Incumbent President Emmerson Mnangagwa is seeking a second and final five-year term in office as head of state in line with the country’s constitution.

Mnangagwa’s main rival is Nelson Chamisa, the 45-year-old opposition leader, who says he has the following to cause an upset.

Here are five reasons why this election is so hotly contested.

Economy

With high unemployment, a local currency that is rapidly losing value against the United States dollar, and hyperinflation that has eroded purchasing power, the economy will be a major determinant in this year’s elections.

Half the population lives in extreme poverty. In addition, the Zimbabwe dollar is trading at $1 to $6,800 US, while annual June inflation stood at 175.8 percent.

Also, the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have caused a surge in the cost of food items. Farmers of key crops such as maize have experienced disruptions in supply lines of commodities such as wheat and fertiliser.

As such, the state of the economy will be a central concern for voters in this election.

Under Mnangagwa’s watch, the economy has shrunk, and analysts are divided about what this means for his re-election bid.

“Unlike in 2018, when [the president] had the advantage of being a hero of the November 2017 coup and the general feeling of giving him a chance, this time around he has demonstrated that … he has no plan to make things better as shown by his failure to even pen a manifesto,” Bekezela Gumbo, principal researcher the Harare-based think-tank Zimbabwe Democracy Institute, told Al Jazeera.

But Eldred Masunungure, director of the Mass Public Opinion Institute (MPOI) and a lecturer in governance and public management at the University of Zimbabwe, disagrees.

“The economy has been in a comatose state [but] … ZANU-PF [the Zimbabwe African National Union–Patriotic Front, Mnangagwa’s party] has supporters who will stick to it. It’s a mystery why Zimbabweans vote ZANU-PF when the party is the author of their misery. It’s a conundrum which requires an investigation on its own.”

Chamisa’s manifesto has promised “macro-economic stability characterized by single digit inflation and stable exchange rates”, a $100 billion economy and the creation of 2.5 million jobs in five years.

Regional stability

Zimbabwe has experienced significant political instability over the past few decades, with violence, corruption, and authoritarianism being recurring themes.

The country’s underperforming economy has led to thousands of Zimbabweans flooding neighbouring South Africa, Botswana, Zambia and Mozambique for better opportunities. An estimated two million Zimbabweans are in South Africa, and that has partly led to clashes between the settlers and the locals in a time of rising xenophobia there.

Piers Pigou, the International Crisis Group’s senior consultant for Southern Africa, sees the status quo continuing.

“Indeed, things could deteriorate on this front, and notwithstanding the weaponising of anti-foreigner sentiment in South Africa and Botswana, it is likely more Zimbabweans will head south,” he told Al Jazeera. “Options for Zimbabweans are limited, and the current economic trajectory is unlikely to mitigate such circumstances for the majority.”

“This is unlikely to have a major impact on stability, but rather will fuel pre-existing tensions.”

Transparency and integrity of the process

Zimbabwe’s elections since 2002 have been marred by massive electoral violence that has left more than 500 dead. In 2008, more than 200 opposition supporters were killed, according to Amnesty International.

Six people were killed in August 2018 when protestors demanded the announcement of election results amid fears that they would be rigged in favour of the ruling party, which has been in power since independence in 1980.

In Zimbabwe, every election has been disputed since 2002. For decades, activists have called for reforms to enhance the independence and effectiveness of state institutions, as well as the transparency of the electoral process.

An Afrobarometer survey in Zimbabwe showed that only 47 percent of Zimbabweans trust the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) to conduct credible elections in 2023. The survey also revealed that trust in the ZEC is generally weak among Zimbabweans, and only a minority of citizens consider the 2018 elections to have been free and fair.

“These circumstances suggest that at best we can expect a continuation of the status quo, selective repression and the theatre of reform,” Pigou said. “I don’t think the elections will resolve anything. External players will only get involved if there is widespread violence.

Social services

For the majority of Zimbabweans, access to quality healthcare, education, and basic services is non-existent. Public hospitals are poorly equipped and may not have essential supplies and drugs.

Mnangagwa, who has blamed the state of the country on sanctions imposed by Western countries due to the fallout from controversial land reforms in the early 2000s, says his government has made strides in infrastructure development and power generation and has grown the mining economy from $3bn in 2018 with hopes to generate $12bn in revenue by the end of 2023.

Corruption

Corruption has been a long-standing problem in Zimbabwe and has eroded public trust in the government. Just this year, a four-part documentary series by Al Jazeera triggered outrage in the country.

The series exposed how huge amounts of gold are clandestinely smuggled every month from Zimbabwe, Africa’s sixth-largest gold producer, to the United Arab Emirates, aiding money laundering through an intricate web of shell companies, fake invoices, and paid-off officials.